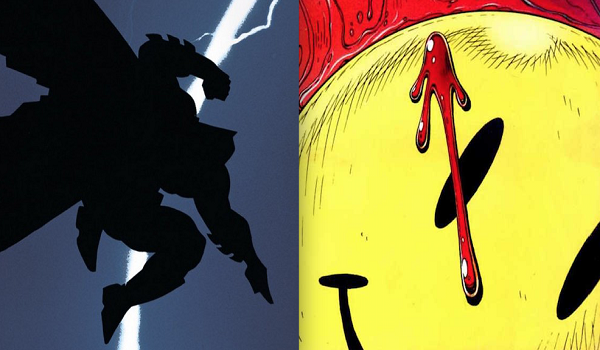

In thirty years the impact of Alan Moore‘s Watchmen and Frank Miller‘s The Dark Knight Returns is still felt. These radical works hit the comic medium in ways where the vibration touched every area of popular culture. This year’s Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice so overtly represented Miller’s Batman that director Zack Snyder even threw in some dialogue from the comic to paint as explicit a picture. DC’s new Rebirth launch has gone so far as to say Dr. Manhattan is responsible for the now frowned upon New 52. The integration of these two innovative titles into mainstream stories keeps their legacies at the forefront of everyone’s creative mindset. And while DC is claiming to reignite the hopeful brightness that existed pre-Moore and Miller, it’s evident these gamechanging comics cannot be erased. They elevated stories of costumed characters out of juvenile privacy where what were once children’s books could create socially conscious tales with appropriate maturity. It’s difficult to imagine things like Comic Con or shared cinematic universes without Watchmen or The Dark Knight Returns. The deconstruction of superheroes in these works, presented with such sophistication, defined a new standard for fantastical storytelling.

In Watchmen, the social and political issues juxtapose the commentary of superheroes and the genre as a whole. Moore challenged the notion of bright colorful characters realized uniformly since the Golden and Silver Ages of comics. He gave us flawed characters damaged by alcoholism, vengeful lust, and sexual violence. And all of these characters mirrored DC’s lineup: Dr. Mahattan as Superman, Nite Owl as Batman, etc. But what makes Watchmen such a pivotal piece in comic book history is the supreme level of writing. Adding rape into a novel with pictures and word bubbles may have attracted attention, but Moore’s storytelling doesn’t exploit such sensitive ideas. If anything, he taints the perfectionism of superheroes by placing them in a reality that mirrored the time of its inception. Moore, who earlier breathed new life into Swamp Thing, meticulously crafted a comic where panels mirrored one another and his unconventional approach to narratives, including newspaper clips and comics within comics, invited a more advanced audience. It’s a title where multiple reads reveal more and more layers of characterization and emotional insight. It’s no small achievement that Watchmen is one of Time’s All-Time 100 Novels.

While Moore’s characters were not direct representation of DC heroes, their parallels are hard to miss. The simplicity of flawless heroes without any sense of repercussion was challenged by Moore’ reflection of the America of the ’80s. No more were superheroes existing in some fairy version of our world, they were in our world. Products of post-Vietnam War and threats of nuclear annihilation. Moore’s fascination with sexual violence would be explored further through actual DC titles such as his infamous Joker story The Killing Joke. And The Killing Joke was not some one-off, what-if, Elseworlds story. It became canon in the Batman universe with the consequences of Barbara Gordon affecting her permanently.

Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns has carried the reputation of best Batman story ever for quite some time. Just as socially topical as Watchmen, Miller’s story gave us a true Batman tale filtered through the lens of media perception. It gave a world where superheroes became obsolete and an older Batman is forced out of retirement due to the overwhelming devastation of corruption and evil. Superheroes are generally ageless, timeless characters, so showing them out of their prime in a world growing bleaker by the day gave a harrowing depiction of The Dark Knight. Though this grim depiction succeeded at two things: It brought the character back to the original intent of Bill Finger and Bob Kane, and it wiped away the sour taste of Adam West‘s take on the character.

It would seem that Tim Burton‘s darkly stylized Batman took some inspiration from Miller’s interpretation, having preceded it by only a few years. It doubled down on Batman’s vigilantism and also gave us the ultimate showdown with Superman, played as a Government puppet ordered to take him down. This brutal, unhinged Batman was so far removed from “Na-na-na-na-na-na-na-BATMAN” you’d think it was a different character. This character was cold, devoid of compassion or remorse, and has since been the standard for how Batman has been interpreted. Miller brought the character to the absolute brink (and later fell off it with All-Star Batman & Robin) and reinforced a Batman who was more vigilante than role model. Miller gave us superheroes who were difficult to root for, pushing the boundaries of justice in harshly violent panels where death was no longer a thing of implication.

The grit and grime of these two comics placed the medium in a permanent shadow. But not a shadow where hope and justice were forever tarnished or removed from the ideologies of these heroes. Moore and Miller presented comics for mature readers, leading to distributors like Vertigo and Image where titles did not have concerns of content. Without these two works, it’s possible superheroes would still be limited by simply narratives targeted at the youth. Thankfully, comics can still be enjoyed by kids. The audience has simply expanded.

What do you think of Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns? Do you see Alan Moore and Frank Miller’s influence in comics today? Let us know in the comments or on Twitter!