If there was a company that can best serve as a gateway into Japanese animation, it is Studio Ghibli. Animation legend Hayao Miyazaki, the late Isao Takahata, producer Toshio Suzuki, and publisher Yasuyoshi Tokuma founded the studio in 1985. Following the success of Miyazaki’s film Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, the studio produced beautifully crafted movies including Spirited Away, My Neighbour Totoro, and Castle in the Sky.

Known for their fantastical stories, lively characters, breathtaking animation, and scores composed by Joe Hisashi, Studio Ghibli’s catalogue are lorded as some of the greatest in history. Spirited Away propelled the studio into the limelight with its surprise success at the Oscars, winning Best Animated Feature. The movies gained further attention through the studio’s distribution deal with Disney, though editing was a source of content for both companies, and their alternate views on family appropriation.

Miyazaki and Takahata have become household names, known for their gift for storytelling and strict sense of perfectionism in their craft. Both were veteran animators and directors prior to founding the studio, Miyazaki finding success with The Castle of Cagliostro in 1979.

This year, Netflix began adding twenty-one of Studio Ghibli’s films to their library (United States excluded). To celebrate this legacy, we will be reviewing every single Studio Ghibli film. Each volume will collectively review the movies released on Netflix, as well as the remaining films left out of the catalogue (e.g. Grave of the Fireflies).

We shall be reviewing the English releases, examining how each was handled by Disney and other companies. Not every Studio Ghibli has received a dub, but will be included nonetheless.

Disclaimer: The following reviews may contains spoilers for Studio Ghibli’s movies. Read on at your own discretion!

The Castle of Cagliostro (1979)

Hayao Miyazaki’s directing debut was with The Castle of Cagliostro. The film is based on Lupin III, a long-running Japanese franchise. Lupin III is the titular phantom thief, a descendant of Arséne Lupin, from the French novels by Maurice LeBlanc.

Lupin has never been caught, going on crime sprees and capers with his partners Jigen and Goemon, crossing paths with female fatale Fujiko, and evading his “nemesis” Inspector Zenigata. Miyazaki and Takahata directed episodes of the 1970s anime.

In most versions of Lupin III, Lupin is a scheming and lecherous thief. In the film, he is portrayed in a more favourable light, being somewhat honourable, his more apathetic traits being swapped out for charm. Such changes were made to the other staple characters.

Lupin and his cohorts get involved in the politics and mysteries of Cagliostro. Lupin and Jigen launch a rescue mission-meets-heist upon the Castle of Cagliostro after encountering Clarisse, a runaway bride. Her groom, the evil Count Laraze d’Cagliostro wishes to unite their family branches, to fulfill your standard prophecy, and unlock the castle’s secrets. Lupin has personal ties to Clarisse, plotting to save her and to seize the castle’s fortune.

Several of Miyazaki’s staples would surface in the film. The level of detail in Cagliostro is beautiful and breathtaking; an example every Studio Ghibli film would follow to superb perfection. The skies in Miyazaki’s movies are a little bit bluer compared to other features.

The film features a lot of great comedy, slapstick, and a fantastic car chase in the opening act. The movie’s finale, set atop a clock tower, has gained homages in the likes of Batman: The Animated Series and The Great Mouse Detective. The movie has had two English dubs, the first by Streamline Pictures, which is available on Netflix.

Castle in the Sky (1986)

Castle in the Sky is the first official release by Studio Ghibli, setting the bar for the studio’s artistic quality. You might call it an epic; a fantastical action-adventure telling a lovingly crafted story of strength, love, and courage. The visual, steampunk aesthetic influenced international pop culture. The film is inspired by Gulliver’s Travels and Miyazaki’s 1978 anime Future Boy Conan.

A young girl named Sheeta, kidnapped by evil government agents, becomes the target of sky pirates who attack her prison airship. Sheeta falls out an airship window, but her magic pendant floats her down to a Welsh-inspired town, where she is caught by a boy named Pazu. Both are united by their quests to find Laputa, a legendary flying castle, said to have had been home to a long gone civilization. They go on the run to find Laputa, chased by the sinister Colonel Muska, and the sky pirates led by the feisty Captain Dola. The pirates later become friends to Sheeta and Pazu.

Castle in the Sky has plenty going for it. From the action-filled, high stakes story, to the lovable characters, to the superb soundtrack by Joe Hisashi. The designs of Laputa itself and the surrounding world are beautiful, richly detailed, and became another staple of Miyazaki’s works.

In regards to the English dub, it closely follows the story with little changes. Anna Paquin does particularly well as Sheeta, though it is Mark Hamill and Cloris Leachman who steal the show as Muska and Dola. Leachman does shout a lot of her lines, but it fits well with the character.

My Neighbour Totoro (1988)

Totoro is the studio’s most famous character and mascot. My Neighbour Totoro, is a sweet-natured fantasy film telling a small story about childhood. In 1958, sisters Mei and Satsuki move to the Japanese countryside with their father, to be closer to their hospitalised mother. They move into a rickety old house occupied by living soot sprites (or Susuwatari), finding the huge camphor tree overlooking their house is home to Totoro, a friendly forest spirit.

Totoro is never portrayed as scary or intimidating, but goofy, amiable, and childlike in his own way. Another character is the grinning Catbus, who got its own short film seen at the Studio Ghibli Museum, revealing a whole species of vehicular felines.

Satsuki and Mei are voiced by Dakota and Elle Fanning; both being sisters, their interactions come off as natural. Satsuki often acts as a sponge to Mei’s outbursts, mature for her age, but can be excitable and childish. Mei, is, well, a toddler; bratty at times, but curious and hyperactive. The girls’ interactions with Totoro and the Catbus are the highlights of the films. Neither are afraid of Totoro, despite his large size. The bus stop scene remains one of my favourites in animation. It’s just so wonderful watching Totoro discover the miracles of an umbrella. The girls’ father never once dismisses or questions their belief in Totoro, accepting their make believe with his own enthusiasm.

The movie is set in a bygone era of Japan, using a rural setting to explore childhood innocence. Art director Kazuo Oga brought this “satoyama” environment to life with extravagant use of water colours. There is a sense of nostalgic fun seeing the children playing outside, exploring the world around them in their new house and garden.

There is no villainous threat, action scenes (sort of), or physical peril. The third act does take a sudden serious turn, though it benefits both Satsuki and Mei’s characters. My Neighbour Totoro’s greatest strength is its celebration of childhood, and the benignity of a world wish to return too. It could best be compared to Winnie the Pooh, simply warm-hearted and cheery.

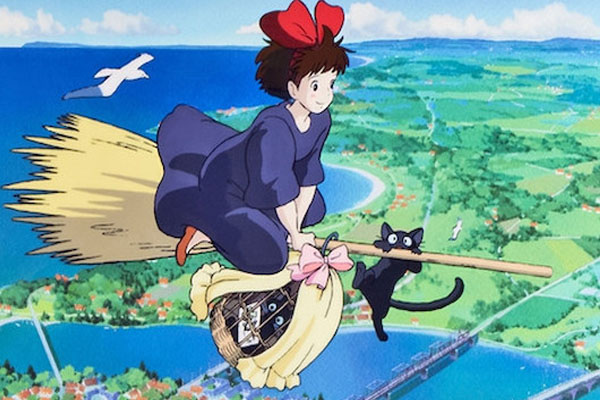

Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989)

Kiki’s Delivery Service is based on the novel by author Eiko Kadono. Although I never quite gained an attachment to it like other Miyazaki films, it can’t be denied that Kiki is one of the studio’s best works.

Kiki, voiced by a fantastic Kirsten Dunst, is a young witch who must embark on a traditional journey of self-discovery, as all witches must. Accompanied by her snarky black cat Jiji, voiced by the late Phil Hartman, Kiki settles in the port city Koriko and gets a job as a bakery’s delivery girl. Kiki goes through a series of personal struggles as she tries to find her place in the world, dealing with responsibilities, friendships, and a rather crushing existential crisis tied to her self-belief.

The movie’s themes of transitioning to adulthood are played out without blemish. Kiki wishes to fit in but stand out at the same time, finding her status as a witch the source of curiosity and distrust. She is befriended by Tombo, an aviation enthusiast (who bares a passing resemblance to Where’s Wally). Kiki’s own desire to avoid vulnerability is her primary obstacle, and when faced with self-doubt, she loses her magic. Jiji acts as a voice of reason for her, but loses his ability to talk when she doubts herself. Kiki wishes to be independent, committed to her convictions and ideals, but can be stubbornly fierce and argumentative when need be.

Kiki tries to balance tradition with the contemporary world. She honours the traditional witch’s black attire, broomstick, and cat, but wears her iconic red bow, and carries a radio with her. She lives in a quaint bakery, and appears to eventually find comfort in the countryside than the bustling city. While she grows to like Tombo, she is put off by his intimidating city friends, reflecting on her own image and identity. The finale is exciting, if a little sudden, though has some clever payoffs and set ups scattered earlier in the film.

Only Yesterday (1991)

The last Studio Ghibli film to receive an English dub, Only Yesterday invokes memories of childhood in an intimate, low key drama. The film was released in 1991, but would not receive a western release for another twenty-five years. While Disney dubbed most of Ghibli’s films, they missed this one, likely because it involves talk of menstruation. Ironic, considering Disney once released a 1940s short film about the very subject. The movie was directed by Isao Takahata, who had a fantastic talent for telling compelling dramas through beautiful animation.

The film follows Taeko, a 27-year old unmarried office worker, who goes on holiday to her brother-in-law’s countryside home to escape the rat race and familiar demands to settle down. Her journey invokes memories of her 10-year-old self, dealing with friendship, romance, family, and school days. These memories often stir Taeko’s adult mind, as she tries to decide what to do with her life. The narrative switches back and forth between 1966 and 1982.

It is almost impossible to watch Only Yesterday without stirring one’s own childhood memories. Certain things Taeko experiences certainly have happened in our own lives. These flashbacks are played out with a dreamy quality, created through washed out colours, with more simple character designs and details. The film carries the traditional presence of gorgeous, detailed scenery, though these are more present in the 1982 scenes.

Surprisingly, a lot of the flashbacks from Taeko’s childhood are left unresolved. In one segment, she learns the school’s baseball protégé has a crush on her, although after a rather sweet scene together, he disappears from the movie. This relates to her memories being how she interprets them, as no memory is so vivid.

Another topic in the film is the conflict between tradition, conformity, and new trends. Taeko lives in a family that balances Japanese traditions, whilst being open to outside influence. A notable scene is where the whole family tries an exported pineapple, which was pricey in those days, but find it rather underwhelming. In another scene, Taeko’s stoic yet gentle father actually slaps her for running outside in socks, which in Japan, was the equivalent of being in your underwear. It is a hard scene to watch, but her father is visibly shocked by his own actions. Taeko also mentions it was the only time he struck her.

Taeko expresses much of her love for country life through internal monologues and accompanying scenes. However, we never see how she developed such a love for her in-laws’ fascinating way of life. Occasionally, the film steers into heavy-handed exposition about the Japanese agricultural industry, which is a little vexing yet educational for western audiences. Daisy Ridley and Alison Fernandez voice the adult and child Taeko respectively, both giving great performances. If there was an odd duck, it is Dev Patel as Toshio, Taeko’s love interest. His British accent stands out, especially when Daisy Ridley has put on an American accent. Still, there has yet to be a bad performance in these films, as Only Yesterday truly delivers.

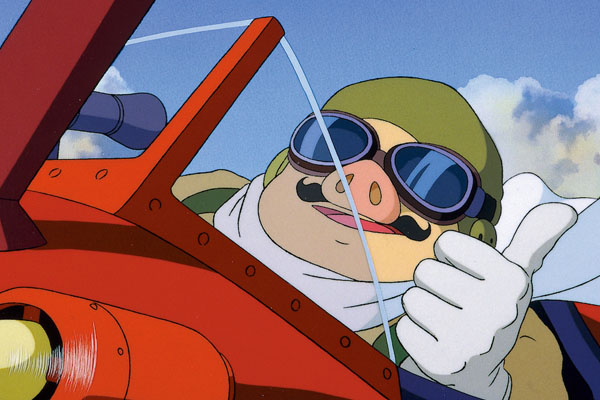

Porco Rosso (1992)

This high-flying action-comedy could easily have worked as a straight-faced historical film. What makes it even better and equally enjoyable is that its protagonist, Porco Rosso, is a pig. Porco is an Italian veteran WWI pilot and freelance bounty hunter, chasing air pirates around the Adriatic Sea. Through a curse, Porco has been transformed into a pig, though no one seems to mind. Michael Keaton delivers one of his best performances as the titular character, playing Porco as gruff and cynical, yet courageous, romantic, and secretly soft-hearted.

The curse itself relates to Porco’s cynicism and own self-imposed guilt during the war, fleeing to avoid enemy fire and unable to save his squadron. Porco tries to keep emotionally distant from other characters, but his good heart and sense of honour chip away at his reclusive roughness. He is close friends with Gina, a restaurant owner who is the widow of his late war buddy, voiced by a well-cast Susan Egan. There is a sweet-natured underlying romance between the two, though their union is only hinted at.

Porco’s bi-plane is damaged by the arrogant American pilot Donald Curtis, as part of a deal with local air pirates. Porco gets his plane to Milan (Truro in the original) to have his long-time engineer Mr. Piccolo fix it. The task falls to Piccolo’s young, ambitious granddaughter Flo, who Porco adopts as his sidekick. The two make a great duo, with some great banter provided by Keaton and Kimberly Williams-Paisley.

By far the highlight of the movie has to be the dogfights and airbourne action scenes. Hayao Miyazaki’s love for planes really shines in Porco Rosso. As usual, the detail and accuracy are superb. The dogfights, chases, and one truly spectacular escape scene are all exhilarating, tense, and, of course, masterfully animated.

The movie was originally planned to be a short in-flight movie for Japan Airlines, based on Miyazaki’s manga The Age of the Flying Boat. Though partially set in a fascist Italy, the movie adopts a more pleasurable look on the country. This interpretation is believed to be based on a Japanese artistic concept, where Europe was portrayed as spectacular, to establish a distinct cultural impression of the continent, and maintain a separate identity for Japan.

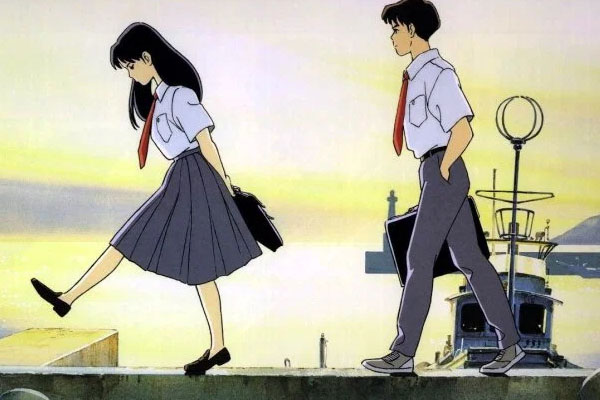

Ocean Waves (1993)

The only television film created by Studio Ghibli, Ocean Waves is the only film yet to have an English dub. The movie was an opportunity for the younger animators to make their own film, though on a cheaper budget and for television. The film was directed by Tomomi Mochizuki, also known for directing anime like Creamy Mami and Ranma ½. It was written by Kaori Nakamura, based on a 1990 novel of the same name by Saeko Himuro. The project, however, went over budget and over schedule, leading Mochizuki to develop a peptic ulcer.

Ocean Waves could be dismissed as a historical footnote, but is an important piece of Studio Ghibli’s history. It is a slice of life story about a high school love triangle, and the school reunion that occurs several years later. Taku Morisaki, a good-natured lad, and his best friend Yutaka Matsuno, both fall in love with new girl Rikako Muto.

Rikako drags Taku into her shaky home life after scamming him out of 20,000 yen, which she then uses to pay for an unplanned trip to Tokyo to visit her unfaithful father. Rikako can be unpleasant at times, acting like what could be best described as a bad girl, but her reasons and actions draw from her unhappy childhood. A big part of Ocean Waves is the use of adolescent perspectives, going through a very harsh, realistic look at teenage relationships. Taku, Yutaka, and Rikako repeatedly become the subject of school gossip, with the expected fallout afterward, caused by confused understandings and impulsive reactions.

The film is mostly uneventful, though never dull, sporting some decent animation, the expected lush background detail, and has its own unique pallet. Though not quite as engaging as Only Yesterday, Ocean Waves could be dismissed for its cheaper budget and more simpler story, but has enough to keep it going. The movie had little impact on the television audience of the day, but like the tide, opinions change, and I am glad Netflix included the film in its catalogue.

Tales From Earthsea (2006)

Often considered the black sheep of the catalogue, Tales From Earthsea was released in 2006, directed by Goro Miyazaki, Hayao’s son. The film is an adaptation of Earthsea, authored by Ursula K. Le Guin, a highly regarded fantasy novel series. There are six books, featuring a prominent culture of black, red, and brown-skinned peoples, and themes of man’s relationship with death. I have never personally read the books, so cannot genuinely compare and contrast the film to its source material.

Hayao Miyazaki pursued the rights to Earthsea for years, but Le Guin dismissed his requests, believing his animation style matched that of Disney. Twenty years later, after watching My Neighbour Totoro, Le Guin came to admire Miyazaki’s work, giving him the rights. But, at the time, Hayao was working on Howl’s Moving Castle, so the role of director fell to his son Goro.

Earthsea has a distinctive use of name-based magic, where the knowledge and use of a true name can equal great power. Such power overshadowed the movie, with Goro facing scrutiny based on his father’s name and legacy. Both his father and Le Guin expressed disappointment in Goro’s involvement, though for different reasons. Hayao believed Goro lacked proper experience to be a director, while Le Guin had expected Hayao to be director. Overshadowed by his father’s legacy and critical, perfectionist’s eye for detail, it must’ve been hard for Goro Miyazaki to make the film.

The film cherry picks elements and characters from the six books, making an original story that doubled as an adaption of Hayao’s manga Shuno’s Journey. A bit of a strange decision. After murdering his father and stealing his sword, Prince Arren wanders the world, specifically a realm where the natural balance of man and magic is falling apart. Arren winds up in the company of archmage Ged or Sparrowhawk, voiced by Timothy Dalton, who is looking to solve the unbalancing. Arren later rescuers an enslaved girl, Therru, who runs off, appearing later as the ward of Ged’s friend Tenar. The angsty prince is haunted quite literally by a shadowy alter ego, responsible for his father’s murder and lust for violence.

During all this, our villain is a sorcerer named Cob, played by Willem Dafoe in one of his most unnerving roles. He is the mastermind behind the world’s misbalance, in order to breach the door between life and death to gain immortality. A bit of a generic motive, though Dafoe’s performance is so creepy, it makes your skin crawl. His goal and methods of achieving it are vague and arbitrary, which unfortunately is a large issue with the movie’s plot.

There are many questions that need asking and answering. Arren’s act of patricide is a great way to open the film, but the reasons behind it are never explained. What was their relationship like and why did Arren feel it was needed to murder his father and steal his magically sealed sword? It relates to his alter ego, but then this mystery stalker turns out to be disembodied light, while Arren’s darker vices are drawn from despair. Or something like that. At the end of movie, Therru turns out to be a dragon in disguise, her power unlocked with the uttering of her true name. Arren has a true name too that Cob uses to brainwash him. Why? Who knows? The books presumably answer all of these questions, but sadly they are absent from the film.

When shown a private viewing of the film, Le Guin told Goro Miyazaki that she liked it, but it wasn’t her book. Hayao himself left his own screening for a cigarette break, commenting that the movie took an eternity to watch. An unfaithful adaptation is one thing, but a film plagued by discontent and disapproval from people with little faith in its creators is just gloomy. Still, the movie upholds the lofty standards of the studio’s animation quality. The best scene might be Therru’s melancholic song, which halts the movie to draw the lost, lonely Arren and Therru together. The movie’s dub has some strong performances, particularly from Dalton, Dafoe, and Cheech Marin.

It isn’t necessarily a bad movie, as Studio Ghibli have yet to make such an error. Tales From Earthsea’s jumbled story, and unsettling, faithless production, sadly contributed to its failure. The movie was panned by critics, with the Japanese equivalent of the Raspberry Awards labelling it as the worst movie of 2006; a claim I highly disregard. Goro would find better success, directing From Up On Poppy Hill, one of my favourite Ghibli films, and then the anime Ronia, the Robber’s Daughter.

Which of the Studio Ghibli films are your favourites? How many have you watched on Netflix? Leave a comment below, or on our Twitter feed!