So, this year marks the thirtieth anniversary of Alan Moore‘s magnum opus Watchmen. There’s no denying that this is one of the all-time must-read graphic novels, placing number 2 in Wizard’s 100 best graphic novels as well as being the only graphic novel in Time Magazine’s, “All-Time 100 Greatest Novels,” list. That is no mean feat! But it’s not just about what it achieved culturally; Watchmen has had a lasting impact on comics in general.

Appearing, as it did, smack dab in the middle of the copper age of comics, Watchmen followed an era of comics where heroes were an overwhelmingly clean-cut lot. With only a handful of striking exceptions, there was little in the way of moral ambiguity or uncompromising brutality in your Marvel or DC comics. Heroes were paragons of virtue, representing an ideal of human bravery and goodness. Batman had his dark and brooding moments, but he had a moral code. Sure, the tail end of the bronze age brought us the Punisher and Wolverine, setting the stage of the age of anti-heroes that continues to this day, and Frank Miller brought us a Daredevil who was darker and more brutal than ever before. By 1986, the world was not just ready, but begging for a comic that spoke to the mood of the era.

The Power of Character and Context

For those of you too young to remember, the 1980s were a time of mixed emotions; economic prosperity on the one hand and the constant fear of mutually assured destruction on the other. There was a pervasive fear of crime, particularly in the United States, and all of this fed into the world that Moore and Gibbons created. Obviously there are major changes, like Richard Nixon ruling the USA in his third term, but these just act to exaggerate the culture that produced the protagonists. This political climate of constant fear and civil unrest shapes the motives of the heroes and the villain, something that modern comics (particularly Marvel) have since used as a key plot device in their events, such as “Civil War” and more recently “Standoff”.

But Alan Moore didn’t just create anti-heroes; he created believable, flawed anti-heroes. People whose only powers were a willingness to do what others wouldn’t, to transgress lines that society was too scared to cross. For example, let’s talk about Rorschach. Ask anyone who’s read Watchmen and they will almost certainly talk about Rorschach first. And there’s a reason for that. Of all the flawed, tragic characters in a book of flawed, tragic characters, Rorschach stands out. He’s the single most popular character in the book, not in spite of his personality flaws, but because of them. Maybe it’s because he represents the darkest urges and feelings that live in all of us, he does the things we want done, and he does them because they “need to be done”. Rorschach is almost a prototype for characters like the modern age Moon Knight; mentally unstable but relentlessly driven.

Apart from Dr. Manhattan, the entire cast of Watchmen consists of regular human beings. Not super-powered, not chiseled demi-gods. They’re doughy or skinny people. People who want to make a difference to the world, motivated by the same forces that drive all of us in our everyday lives. Alan Moore made heroes accessible and truly relatable. This resonates in comics even thirty years later. Even super-powered heroes have complicated personal lives, with writers making huge efforts to explore the motivations of the characters they write, and the relationships they have.

Creative Innovation

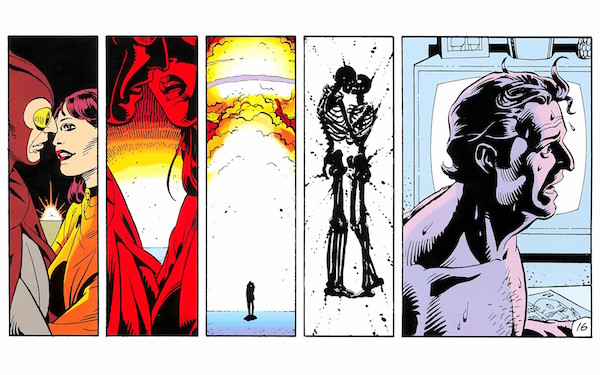

Let’s not forget the contributions made by Dave Gibbons, though. Gibbons’ art style in this book has been hugely influential, particularly in the anti-hero genres of comics. There’s something about the sharp lines and deep contrasts that speaks to the grittiness and grounded reality of anti-heroes. The visual language of the book is something that has been mimicked repeatedly, from Batman to Preacher. But the format of the book is unique, something that has never been successfully attempted by anyone before or since. Gibbons’ use of the comic format as a plot device, when Dr. Manhattan explains how he experiences time and space, is something special. The whole sequence is played out in such a way that he prophesies everything that will happen, and you can flick back and see it happening. It lets you see through the character’s eyes.

A True Legacy

As most people know, Alan Moore is not crazy about the legacy that his works have created. In an interview with now defunct website mania.com (via www.inverse.com) talking about comics post-Watchmen, Moore said:

They’ve lost a lot of their original innocence, and they can’t get that back. And, they’re stuck, it seems, in this kind of depressive ghetto of grimness and psychosis. I’m not too proud of being the author of that regrettable trend.

Like it or not, though, it’s an undeniable fact that Moore’s work, and Watchmen in particular, has helped to shape the face of modern comics. As someone who was a child when Moore was at his peak, I grew up in a world where Alan Moore had already made his mark. It had already permeated everything by the time I had started to pick up titles like Wolverine or X-Men, so I never noticed until I took the time to do some research.

So While Watchmen didn’t single-handedly change comics, it did build upon a bedrock of growing darkness in comics, and provide one of the greatest narratives in comic history. Maybe its biggest contribution is that it helped to legitimise comics as an art-form and mode of storytelling, to elevate it above “funny books for kids” and pave the way for the current renaissance in comics we are experiencing now.

I’ve had my say, now have yours. Do you think Watchmen is influential, or over-rated? Maybe you think Alan Moore is a visionary, or maybe insane? Sound off in the comments or send us your thoughts on Twitter!