How do you succintly describe and neatly comparmentalise a comic that’s vehemently against being pigeonholed in such ways? That’s the challenge myself and every other reviewer faces when attempting to write-up Lucy Sullivan‘s debut graphic novel Barking. A semi-autobiographical account of the empathy and the horror of mental illness, Barking is many things: grotesque, riveting, complex. If Barking can be summarised at any level, it’s that it’s neither good or bad. It’s beyond such thinking.

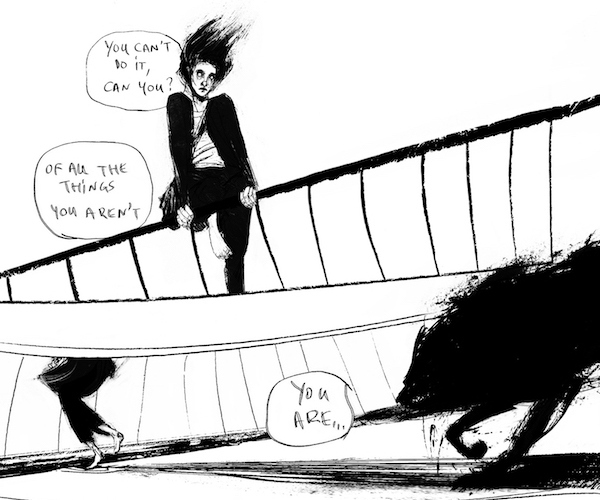

The first thing that strikes you about Barking is how it looks. The visual chaos that’s strewn across every page reads as a direct, obvious metaphor for the internal battles fought against depression. Diving deeper into the comic, you soon realise how difficult it is to stay afloat in Barking’s violent torrent of shape and design. Barking isn’t so much constructed as it is destructed. It sees the comics medium as something to be broken down and rebuilt into something unrecognisable yet gripping and relevant. Barking tells the nightmareish story of Alix Otto’s sanctioning into an institution as her mental instability growingly haunts her. Thoughts of suicide and visions of her friend’s death plague her everday life.

With Alix trapped in an unforgiving hospital environment and her grief-induced visions getting stronger, Barking‘s disdain for a broken medical system that’s unable to properly care for those with mental illnesses gives it a further snarling edge. By the comic’s finale, the system remains intact in its brokenness. This is something Barking doesn’t shy away from, it doesn’t offer an answer to any of the problems it illustrates, no tidy resolution, no genuine happy ending. Alix’s grim feelings don’t evaporate as the comic comes to its end. Instead, she starts to understand how to manage and live with those feelings. Sullivan’s story-telling skills are as unforgiving as her artistic style.

By it’s very nature, Barking‘s visual flow is often difficult to comprehend. Indeed, “flow” just isnt the right word here at all. Barking doesn’t flow – it thrases, it writhes, it screams. It arrests you with its chaos. It’s a comic that’s more concerned with cementing you in Alix’s mind, placing you within the centre of this maelstrom. There’s something of a formal narrative convention in Alix confronting her demons, but for the most part, Barking isn’t concerned with getting the reader from A to B. It places you firmly in the middle of A and B, trying to make the reader understand what having depression is like through its barrage of visual emotion, but even then, that vision is blurred. There’s something almost tactical in how you can’t fully comprehend what Barking is trying to tell you, reflected in dialogue and descriptive text written in a scrambling manner, often appearing more like graffitti than regular speech and sometimes obscured completely.

Barking feels like it’s not trying to make sense of depression, but instead show the reader how nonsensical it is. The comic ultimately pins down what can’t otherwise be pinned down, those feelings of mental illness that can’t be fully explained. It’s a violent comic about a violent condition that’s not concered with sugar-coating any aspect of the themes it tackles. Barking is a comic that’s visually terrifying, thematically robust and endlessly absorbing. Make no mistake – this comic will leave you in tatters.

You can discover more about Barking from Sullivan’s website and Unbound. Did you come out of Barking in one piece? Let us know in the comments section below or send us a Tweet!